- Roasting for espresso: Crankhouse Coffee stands for the omni-roast style. When using a FW coffee for espresso, which will have to be ground fine later on, the charge temperature is high and the burner at 100%. This helps the coffee reach the necessary brewing solubility without going dark.

- Roasting for filter: April Coffee adopts a short between batch protocol to keep energy in the drum. The roaster can use a low charge temperature and a staged burner structured even for dense Colombian beans. The method also helps with batch to batch consistency.

- Fermented coffees can be dense, yet the seed exterior might be porous. Roasting a smaller batch can help balance the amount of energy in the drum. There's enough heat to fully develop the beans within a short roast time to preserve the vibrant sensory notes.

This is the last of a two-part series about roasting coffee from Colombia, where the diversity in flavour profilers reflects a multitude of processing recipes.

Part one talks about how the country became a post-harvest innovation hub and broke down how we expect different regions to show on the cup.

Now, roasters Dave Stanton (Crankhouse Coffee, UK) and Joseph Fisher (April Coffee Roasters, Denmark) return with their approach to profiling Colombian coffee.

Both agree that the impact of processing on density is one of the main physical aspects of a coffee that will influence the roast profile. Yet, they have different styles.

See their roast profiles for three different Colombian coffees and find out how the processing method impacts charge and drop temperatures, burner structure, development and even batch size.

Fully Washed Roast: The Basics

The “typical” high-altitude Fully Washed Colombians that specialty roasters are used to is a fairly straightforward roast.

It’s really dense, withstands loads of heat and usually tastes good no matter the roasting style. A well-balanced cup with solid flavours.

Lots of heat is necessary for inner bean development, but this can easily get out of hand.

Joseph recommends “longer roasts” to avoid underdeveloped coffee, combined with “soaking” to control the final temperature. This will produce a more balanced cup with more perceived sweetness.

Unlike underdevelopment, ageing coffee is something that can’t be fixed.

According to Joseph, “We often find that the peak window for green coffee freshness can be shorter with Colombian coffee, as paper or cardboard notes can creep up on you slightly faster than with comparable coffees from other origins”.

Though not quite a profiling tip, considering the right amount of coffee to buy to avoid ageing makes production roasting easier. You also won’t have to change the profile later down the line.

On the plus side, sourcing Colombia to sell at peak freshness isn’t a problem as the country produces coffee most of the year.

>> Read our 2023 Colombia Harvest Report here.

The Crankhouse House Espresso

The Fully Washed Colombia is a key element of Dave’s house espresso, CHX, chosen to bring red fruit flavours such as cherry and plum, as well as acidity, to the cup.

It’s blended with a Natural Brazil on a 40% Colombia to 60% Brazil ratio to ensure creaminess and nuttiness.

Dave's Loring S15 Falcon. He adopts an omni-roasting style (Photo: Crankhouse)

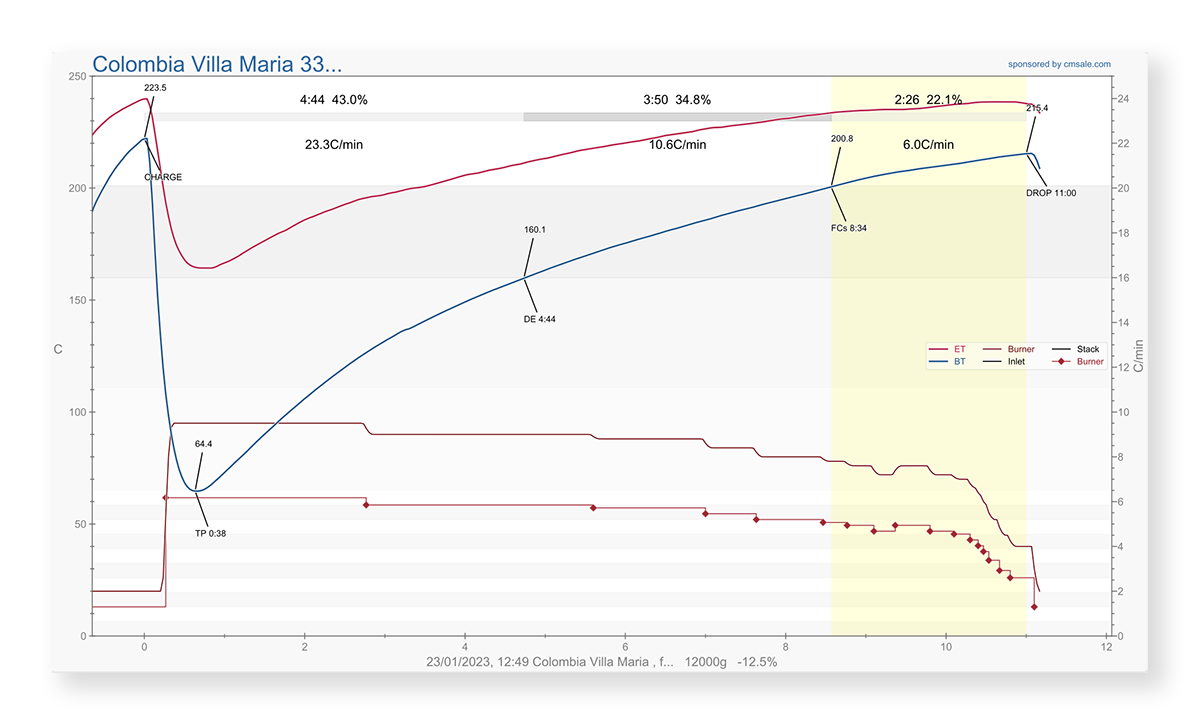

Both coffees are roasted separately in 12kg batches on Dave’s Loring S15 Falcon. To keep the vibrancy of the Colombian, Dave’s drop temperature is high at 240ºC (exhaust temperature) or 220ºC (bean temperature).

He roasts for 11 minutes and 15 seconds. That’s about one minute less than he needs to get a medium roast on the Brazil, which is quite significant considering the second coffee is less dense. The final temperature is 214ºC.

Dave's profile for a Fully Washed Castillo. The coffee was grown at 1,800m - 1,900m

Dave says he doesn’t need to use a soak early on in the roast, as he is trying to keep acids from degrading. “For the first six minutes, [the burner] is running at 100%,” he says.

”That’s so we have enough energy to complete the roasting process within the allotted time.”

He also doesn’t have to worry about scorching as that normally doesn’t happen on Lorings.

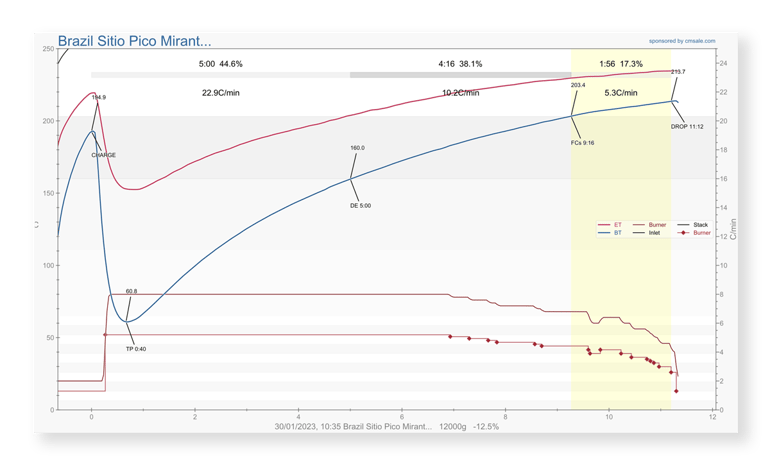

“With the Brazilian [beans], the charge temperature is lower partly because the moisture content is around 2.7% lower, and partly because it’s a smaller bean grown at lower altitudes.”

Dave's Brazil roast is less aggressive due to the coffee's lower moisture content and screen size

Preserving Acidity on Delicate Coffees

The approach is different for Colombian micro-lots, as roasters in Europe favour the fruity and complex sensory profiles created by methods with extended fermentation periods.

Crankhouse has been buying the same Pink Bourbon from a farm in Calarca, Quindio, for the past three years. The process is carbonic maceration.

“The flavour profiles are quite extraordinary, but it’s quite a delicate coffee to roast,” he says.

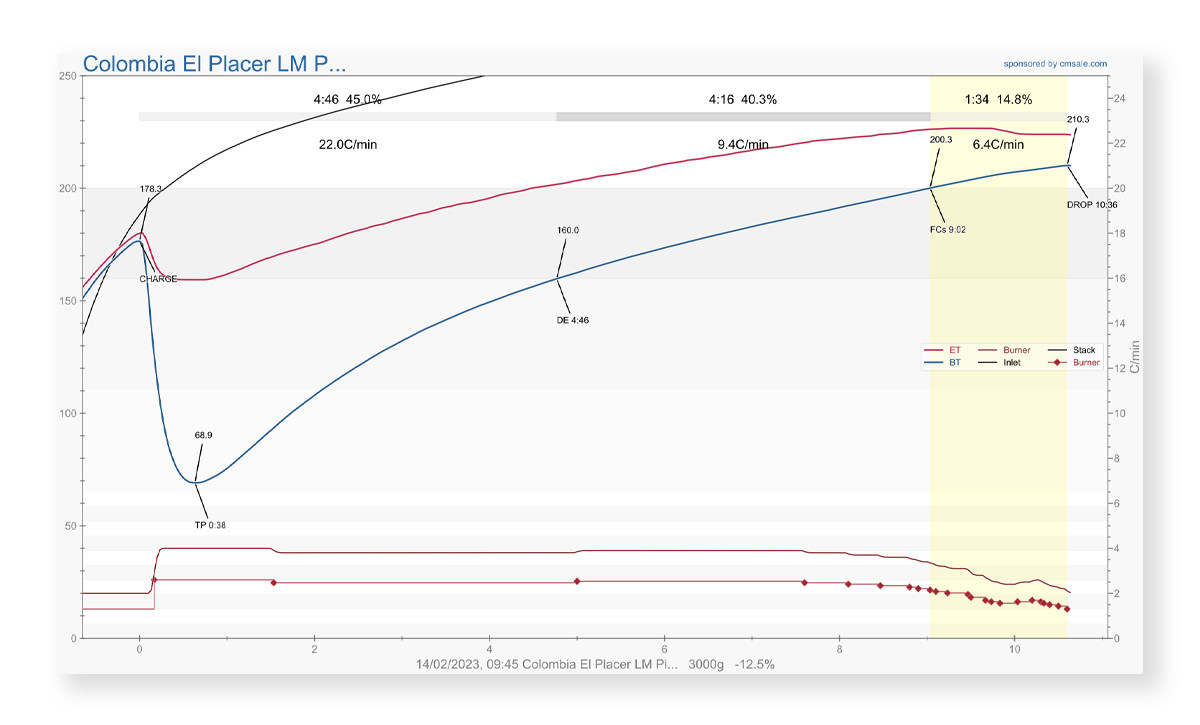

For the Pink Bourbon, Dave goes for lower charge and drop temperatures. This is due to the processing method and the batch size

Having done fermentation courses himself with Lucia Solis in Colombia, Dave explains that the “processing technique makes the outside of the seed less robust, so you may need to be careful not to damage it with too much heat”.

It’s a case of finding a sweet spot, because “if you roast too slow and long then you risk losing some of the vibrant pineapple flavours that were present in the sample.”

Dave roasts his Pink Bourbon in 3kg batches, the minimum load recommended for the Loring S15. Both the charge temperature and the drop temperature are lower than he would use on a Fully Washed.

Batch Size, Consistency & Energy Efficiency

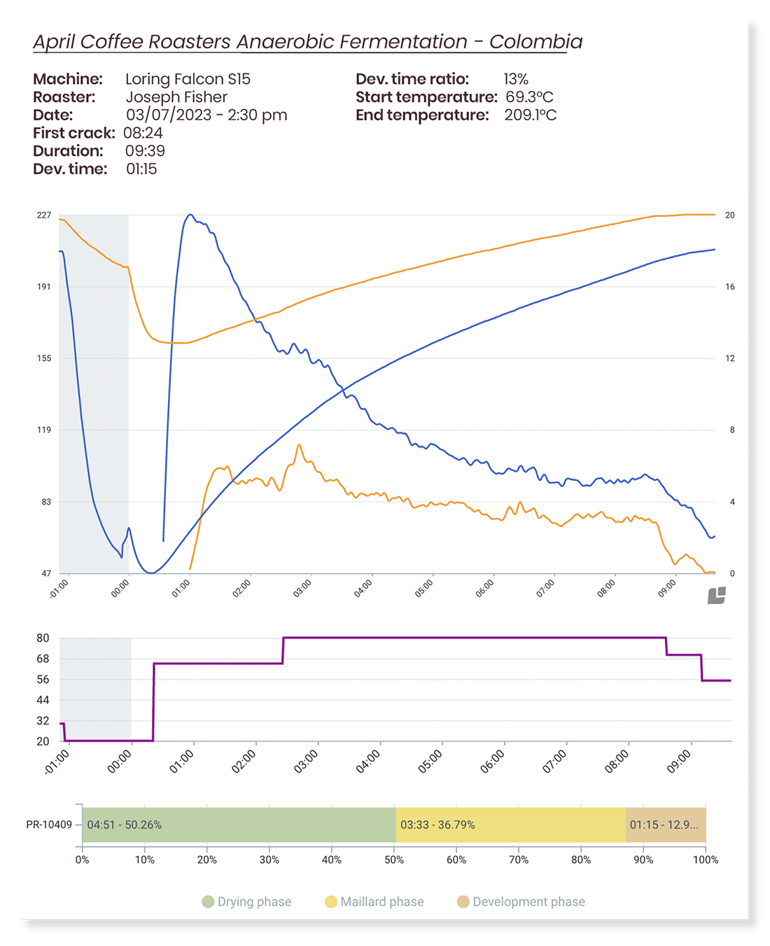

Joseph, who also roasts on a Loring S15, profiled an anaerobic fermentation Colombian for filter in a similar style.

April chooses to roast filters with a low charge temperature. This helps to create consistency in experimental lots and - bonus - energy efficiency.

“The charge temperature is low, however, this reflects the energy carried over from the previous batch,” Joseph explains, adding that the door of the roasting machine remains open for only one minute in between roasts, reducing the time between batches for energy efficiency.

A short between batch protocol helps Joseph keep energy in the drum and charge the roast at a lower temperature and staged burner structure

The Danish roaster says this protocol makes it harder to maintain consistency “as the conditions of the previous roast can have a larger impact on the following batch”.

To balance that, he maintains the same batch size for all roasts and schedules the roasts “in an order that maximises consistency and continuity”.

Fermented Coffee Is Not Always Less Dense...

When thinking about how to best roast Anaerobic Colombia, Joseph was aware that his machine would carry a lot of energy from the previous roast. “I chose to offset this by implementing a staged burner structure of 65% and 80% [gas],” he explains.

“This enabled me to achieve the total duration and approximate phasing times that I was looking for without worrying about either lacking energy when entering the development phase, or having too much energy earlier in the roast and therefore accelerating the drying phase.”

Joseph adds he tries to keep the profile as simple as possible, without fiddling with the gas position too much.

“We find that profiles with fewer variable gas positions taste better, whilst the additional benefit of this philosophy is a more simple workflow which in turn makes consistency easier to achieve.”

Diversity in processing means that the physical attributes of the green have to be considered lot by lot (Photo: April Coffee)

Unlike Dave, and perhaps because the density of the anaerobic beans was still high despite the fermentation, Joseph’s development time on Anaerobic Colombia was slightly longer than his usual filters (1 minute and 15 seconds against 1 minute and 5 seconds).

The same goes for his drop temperature: 209.1ºC for the Colombian coffee compared to the regular range of 207.5ºC to 208.5ºC.

Crankhouse hosts a series of educational cuppings for the industry and the community about different origins and processing methods (Photo: Crankhouse)

During the development phase, Joseph aimed to “balance a reduction in gas with the natural moisture release of the coffee”.

He found that both “density and moisture of the lot remained high and I expected a reasonable release of moisture which wouldn't require drastic reductions in gas position”.

For this coffee, he dropped the gas by 10% after the first crack, followed by an additional 15%, bringing the Rate of Rise from 5,3 down to 2.

In the end, he managed to develop enough sweetness whilst retaining the sparkling acidity provided by the processing method.

As the different approaches seen here show, there are no rules on how to roast Colombian coffee. Given the diversity in processing, the physical attributes of the green have to be considered lot by lot.

We’re dealing with an organic product that’s changing all the time, and there’s never a single correct profile for any single coffee,” says Dave.

It also means that the more you understand how a coffee was processed, the more you’ll be able to judge how to best profile it.

As Dave puts it, “The more care and attention that is paid at every stage, in processing, storage and drying, and of course roasting, the better the final cup.”

There is a wide variety of Colombian coffees with different processing methods on Algrano. Roasters can get detailed post-harvest information directly from producers and understand how that affects profiling.

Let Us Know What You Thought about this Post.

Put your Comment Below.